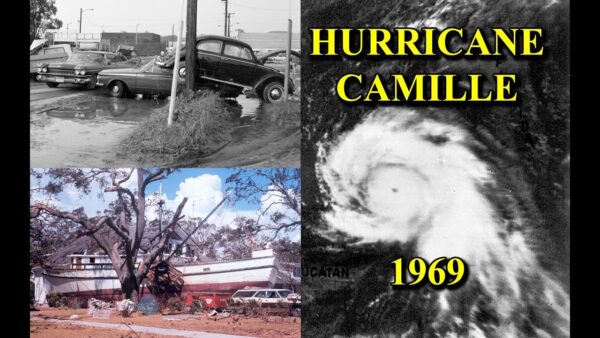

Dispatches from Home – Camille 1969 50 Years Ago August 2019

The crazy, chaotic summer of 1969 is remembered for many things: Woodstock, Chappaquiddick, the moon landing, the Zodiac Killer, and Charles Manson. But for those of us who lived on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, we remember only one thing about that summer: Hurricane Camille. Her very name conjures visions of apocalyptic destruction, heartache, and death.

Fifty years ago, tonight, much of the world that I had known vanished. Gone were many of the quaint things that made the Coast home: Victorian gazeboes and shooflies, grand mansions along the beach, and columned churches. And for months thereafter, gone too were the sounds and smells of everyday life: the wailful mourn of train whistles, the chatter of birds and crickets, the briny smell of seafood from the Point, and honking car horns. However, all that was yet to come though, as I readied myself for church that Sunday morning. The sky was already a strange, yellowish grey. Mom decided to stay home and prepare for the storm, even though it was predicted to hit the Florida panhandle. Dad was flying into Mobile later that day and driving home. Sitting in the choir loft of FBC Gulfport, listening to Dr. John Traylor’s sermon, I knew something was amiss when deacons scurried around asking men in the congregation for assistance. Then I heard the sound of scaffolding being erected. The clatter of hammers against iron and wood distracted from the sermon, as the church’s huge stained-glass windows were covered with thick plywood. Whispers could be heard too; the storm had turned toward us.

Someone interrupted Dr. Traylor’s sermon with the news. He then said a prayer for everyone’s safety, asking for God’s mercy on his congregation. I could not get home fast enough. In my absence, a cousin had called Mom, asking her if she, her husband, and three-year-old daughter could ride out the storm at our house. Mom, of course, said yes. The afternoon was spent readying everything for the storm. We were concerned whether or not Dad would get home before bad weather closed the highway. After some tense hours of worrying, he did. We all gathered in our hallway–quilts for bedding, flashlights and candles, water, food, and a transistor radio. Dad said a prayer. We hunkered down and awaited our fate. The electricity failed at 9:26 that night. Little did we know that it would be three weeks before it was turned on again.

The rain increased, lashing our little house with sheets of watery hail, or so it seemed. The wind intensified. Within hours, the house creaked and groaned, as if it were fighting for its life. The screeching wind pushed hard against the windows; they appeared to breathe. I could see them moving ever so slowly, in and out. The back door did the same thing, pushing against its hinges and lock. Over the wind, though, we heard what sounded like mini explosions. Looking out the window, we saw writhing black shadows silhouetted against the black night sky. The towering pines in our backyard lunged backward and forward. One by one, they would bend, pop back up, bend again, this time almost touching the ground, and then with an explosive crack, would break off about four feet off the ground. We settled back into the hallway for safety, not knowing if we would survive the night.

As the storm raged, Dad turned the dial on the transistor radio, looking for news of the storm. The only station he could find with any clarity was out of Knoxville. As the house shook and the wind screeched, we were serenaded by the Mull Singing Convention. “I’ll Fly Away” was the opening song. Mom sat quietly, as did I. She held me tightly in her arms. My cousin’s daughter giggled and laughed, thinking we’re having a birthday party due to the candles. But what awaited us come the morn was no birthday party. Unlike the great storm of 2005, Camille was a fast-moving storm, which is what saved the Coast from even more destruction.

As dawn broke, it was evident that we had survived a cataclysmic event. Our street, Wilson Drive, was covered in debris. Neighbor’s roofs were damaged. Power lines were down, some still dancing with electricity. The morning heat was like a steam bath, the air dead still. But we had survived; survived one of the greatest natural disasters to hit the U.S. mainland up to that point. Many others did not. In the days and weeks that followed, the normal ebb and flow of life returned to the Coast. Neighbors helped neighbors. Federal and State assistance arrived. The Coast, however, would never be the same again.

Gone was a simpler time and place, so it seems looking back on those days. As I age, I tend to romanticize the past as many do. But to a sheltered, sensitive boy of seventeen, digging through the remains of what was and would never be again, I knew my world had irrevocably changed. The day before, everything was as it should be. Now, the morning revealed something new, something a bit frightening. Camille had awakened something inside me, made me rub my eyes, and see the world for what it truly was and still is. A place with little peace, satisfaction, or happiness unless you are grounded in what you believe; a belief that transcends all of life’s tragedies and pitfalls–a belief in God and Family. To mind simple mind, the world of today awoke on the night of August 17, 1969.