Dispatches from Home: Prophecies, Bad Omens, and a Lucky Pig.

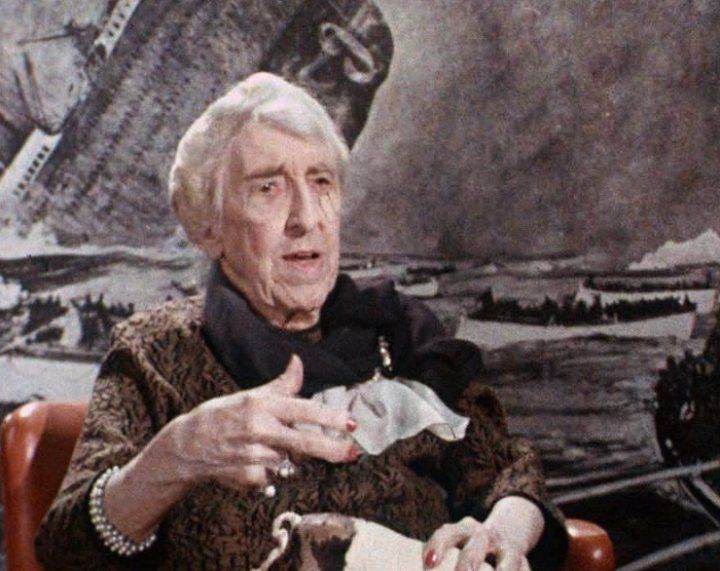

“I don’t believe in fortune-tellers!” Edith said, sitting in the gilded splendor of Madame de Thebes’ Parisian salon, the most famous fortune-teller of the late 19th Century. “I shall predict your fortune anyway,” the lady said in the flickering candlelight, her voice low, her stare intense. “You are about to go through a dreadful experience. You will lose your possessions, many friends, and your singing voice, but you will live for many years to come.” Then Edith remembered the previous year’s prophecy by an aged Algerian fortune teller: “Madame, you will be in a very grave sea accident.” A cold shudder chilled Edith to the bone as she clutched her 1st Class ticket. The ship, the RMS Titanic.

Edith Rosenbaum Russell was 33 when she boarded the Titanic in Cherbourg, France, with her 19 steamer trunks crammed full of the latest haute couture fashions. She was a fashion consultant for the “Woman’s Wear Daily” magazine and purchased the latest seasonal collections from the leading Parisian fashion houses. She was vivacious and high-spirited, her personality addictive. She made many new friends once onboard the Titanic, as well as kibitzing with her old friends. Mr. and Mrs. John J. Astor, the richest man in the world at the time, along with Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff- Gordon, the Countess of Rothes, and of course, Molly Brown were counted in her little coterie.

As Edith approached the Titanic, floating serenely in Cherbourg harbor’s placid waters, suddenly the tender was thrust upward. Its passengers held on to the rail for support. The unfounded turbulence troubled Edith, another by bad omen? When she finally boarded the ship, she asked if she could book passage on another liner. Yes, she could, but her luggage would not follow her. She declined, boarded the ship, and was overwhelmed by its beauty and splendor. Then another incident sent yet another cold shiver down her spine.

The Titanic steamed from Cherbourg to Southampton to receive more passengers. As she steamed out of the harbor, the movement of her vast hull sucked the New York into her path. Only the adroit talents of the harbor’s tugboat captains kept the two ships from colliding. Another bad omen? She reassured herself by remembering what she’d ofttimes been told…the Titanic was unsinkable.

On the night of April 14th, Edith was getting ready for bed when she felt a series of bumps against the ship’s side. She then saw a massive white wall of ice pass by her porthole. Minutes later, she noticed the throb of the ship’s mighty engines had stopped. As time passed, she and other passengers standing at the foot of the grand staircase were told they should don lifebelts and find their way to the lifeboats. Edith dashed back to her stateroom, threw her heavy fur coat over the white satin dress she’d worn that night to dinner, and went on deck. More time passed. The slant of the deck increased. The number of lifeboats dwindled. The time was nearing 2:00 in the morning. The Titanic had only minutes to live.

When the time came to enter her lifeboat, Edith stopped, her face in a panic. “I can’t leave my lucky pig,” she thought. It had been a gift from her mother, who had heard that pigs were considered good luck in France. Edith had promised her mother that she would never be without her lucky pig, which was covered with black and white fur and was the size of a big kitten. She asked her stateroom steward if he would get it for her. He dashed back to her stateroom, wrapped the pig in a woolen shawl, and dashed back on deck. Edith thanked him. She would never see him again. The father of five did not survive the sinking. But the lucky pig saved Edith’s life.

Approaching the lifeboat with the pig under her arm, Edith was frightened. The thought of climbing over the rail and jumping into the boat, hanging about three feet from the deck, wrapped her stomach in knots. She argued with the ship’s officers. In exasperation, one of the officers grabbed the pig mistaking it for a child. He threw it to a lady in the lifeboat; Edith quickly followed.

I’ve often tried to relive that night. What it would have been like to be in a lifeboat watching that massive, floating city sink. Hearing the straining steel bulkheads moan and creak. Watching the ship break apart in a cascade of sparks. Decking shattering in a torrent of sharp splinters. Funnels collapsing, guide wires slicing the air and flesh. And then to hear the screeches and screams of the dying. To hear them thrashing about in the 28-degree water, slowing freezing to death, crying out for help that would never come.

And then I think of Edith and her lucky pig. She stated that once the screams and cries ceased, in darkness, black as pitch, the only sound was a deafening silence. As the night wore on and rescue seemed a dream, fear gripped those in the lifeboat. To help ease their worries, Edith did what she’d often done when she was frightened–she turned the pig’s little tail. The little music box inside played a melodic tune. The rest is history.

However, the prophecies of both fortune tellers came true. Edith was part of the most horrific, peacetime maritime disaster to date. She did lose friends that terrible night. She did lose her possessions. She also lost her singing voice. And she did live long, dying in 1975 at the age of 95.