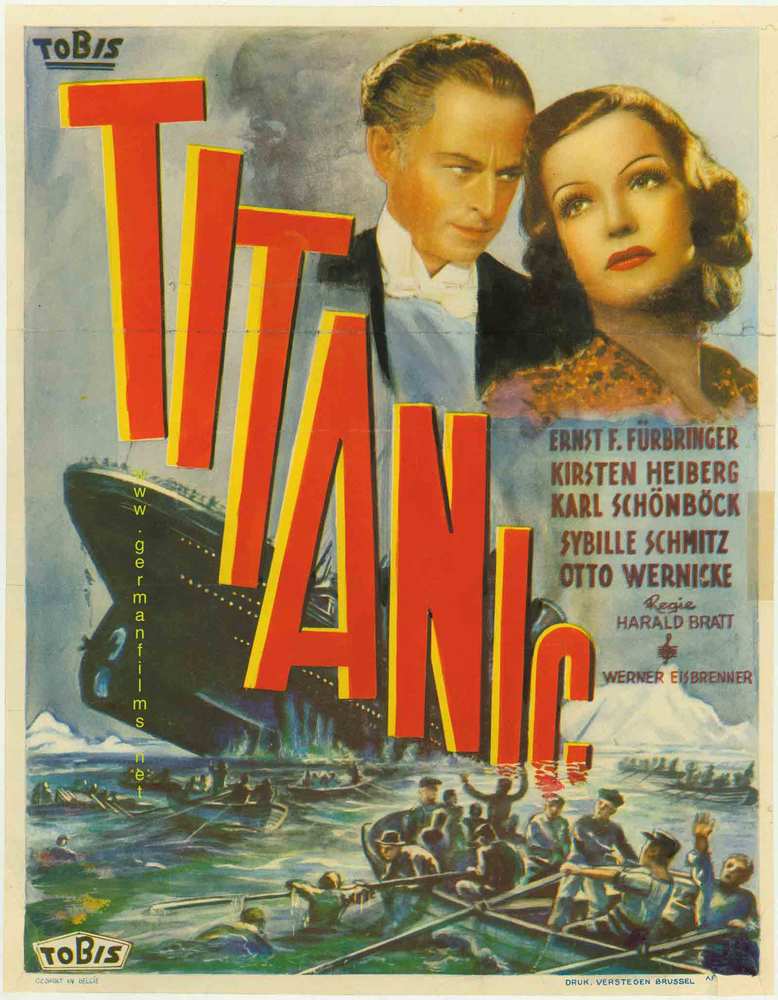

Dispatches from Home: The Nazi’s Titanic.

In the aftermath of the Titanic disaster, the ship became a metaphor for all of society’s misfortunes. The years leading up to the sinking had been excessively optimistic. Rich and poor alike put their faith in technological advances, believing mankind had reached the zenith of its knowledge. As one Titanic crew member stated, “God Himself could not sink this ship.” When news of the sinking raced worldwide, others saw the Titanic as a morality tale peppered with arrogance, vanity, and pride. During World War II, those human failings were the perfect spices needed to help season a propaganda movie by Joseph Goebbels. The Titanic was the perfect boiling pot.

In the Spring of 1942, Goebbels, Hitler’s Propaganda Minister, gave his blessing to the movie’s script, and Herbert Selpin, the movie’s original director, began filming. Selpin was as well-known in Germany as Billy Wilder or Hitchcock was in America. For all the loyal Nazis sitting in darkened movie palaces throughout the German Reich, the movie’s message was intended to show the superiority of German filmmaking and that Allied capitalism was responsible for the Titanic’s sinking. This movie was the first to simply use “Titanic” as its title. It was also the first to combine fictional characters and their subplots with the actual events of the sinking.

The movie’s first hour introduces both the nonfiction and fictional characters. The strangest of which is a German officer serving as part of the Titanic’s English crew. Once the ship begins to sink, his superior bravery and selflessness in saving others are in direct contrast to the British officer’s incompetence and cowardness.

J. Bruce Ismay is portrayed as a conniving shipping magnate who concocts a scheme to save his dying shipping empire (in reality, it wasn’t.) and his own fortune as well. The success of this devious scheme, which also involves wealthy Americans like John Jacob Astor, depends on the Titanic crossing the Atlantic in record time. Convinced that the Titanic is unsinkable, Ismay and the Captain ignore ice warnings from (you guessed it) the German officer. As the ship enters an icefield, Ismay orders it to maintain its breakneck speed.

Viewed through the highly distorting prism of Nazi anti-British/American propaganda, this account of Titanic’s sinking offers little in the way of historical accuracy but was a major cinematic achievement for Goebbels and his little band of Nazi filmmakers. It was the most expensive German film of its time, and its special effects impressed audiences with its visceral authenticity that conveyed the scale and horror of the sinking.

However, this film was a simmering cauldron of production overrides, ego clashes, massive creative differences, and general wartime frustrations. As filming progressed, more lavish sets and costumes were demanded by Director Selpin, along with a slew of German Navy personnel needed to portray passengers and crew. These demands were approved by Goebbels despite the mounting costs and the drain on the wartime German economy.

When Goebbels viewed the final cut, he was not pleased. However, due to its expense and prestige, he allowed it to run in German-occupied Europe but not within Germany. He feared the film would weaken the German citizen’s morale instead of improving it due to its all-too-realistic portrayals of panic and death. Allied bombers were already raining down death and destruction throughout the Fatherland. The audience also saw the fictional German officer criticizing and correcting his superiors. That was verboten in Germany and German-occupied Europe, where unquestioned obedience to the Nazis was a matter of life or death.

Director Selpin also ran afoul of the fanatical Goebbels. Selpin’s personal view of Britain and America was at odds with how Goebbels demanded those countries be portrayed in the film. He was also an outspoken critic of the German military. All of these were big no-nos in wartime Germany. He was denounced by one of his own screenwriters for his unapologetic anti-Nazi sentiment and was arrested by the Gestapo during the film’s production. Within 24 hours of his arrest, Selpin was found dead in his prison cell, apparently having hanged himself using his pants suspenders as a noose.

Goebbels had the death scene secretly photographed and then sent a terse letter to Selpin’s wife notifying her of her husband’s suicide. Despite Goebbels’ attempt to conceal the truth, Selpin’s brutal murder quickly spread through Berlin’s film colony. They were deeply angered by the screenwriter’s denouncement.

Goebbels retaliated by issuing a proclamation decreeing that anyone shunning the screenwriter would personally answer to him and be subjected to the same fate as Selpin. Goebbels also ordered that Selpin’s name not be mentioned on the Titanic set or elsewhere. Werner Klingler, who was not credited, subsequently completed the movie’s production. You can view the original movie clip via YouTube.

As dear Paul Harvey would say, and now you know the rest of the story concerning the Nazis and the Titanic.